Torque/Speed Curves

In this post I’m going to describe our attempt to measure the power curve for the DC motors used in the Solar Dragster race this year. I’m going to be honest, our efforts weren’t really that successful, but I can at least say that I learned some things that might help for next year, and I think the students were able to do some authentic device testing – a part of being an engineer.

Last year I was a bit concerned that the DC motors that we were using in the Solar Dragster Race were not actually outputting the same power. I wanted to devise a way to measure the motor power, and then have each team do their own analysis. I wanted the students to do this without understanding the electrical power parameters involved because we were at this point only looking at motors as being a black box that gets energy from a source and transfers that energy into a rotational device – i.e. an axle, then to a gear, then to another axle, and finally to a wheel. I looked into getting a torque sensor, but quickly found out that these cost a fortune!

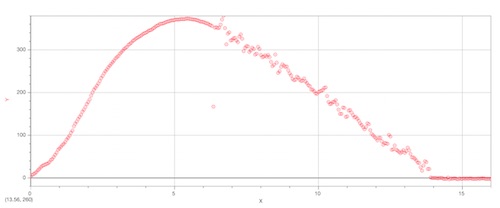

I came across this interesting website from MIT, which was a nice resource for the theory about DC motor performance. The site does a nice job in explaining torque/speed curves, and how the graph of torque vs angular speed is essentially linear for DC motors. That meant that all the students really needed to do was to measure stall torque and the no load speed of their motors and then we would have the torque/speed curve. The website identifies a device that they custom built for testing motors, and it looks interesting, but I didn’t have time to reverse engineer what they had built and unfortunately the images and videos aren’t clear enough to easily understand how the device works – something perhaps for summer tinkering…

One of the issues with the little DC motors that you buy is that the arbor is really small, and it has no index, so its really hard to attach anything. Generally, you have to go with a friction fitting, and I was worried that doing a stall torque test was going to be difficult. Mr. Holt and I designed and printed out a little lever arm to attach to the motors. This little arm could then be attached to a force meter to measure the stall torque and then also used to help measure the rotational velocity using a Photogate. The final “test-bench” looked like this:

The motors were clamped to a lab stand that was then placed so that the little lever arm would rotate and block the Photogate laser as it spun. This is how the students measured the no load speeds. Then they attached a string to the little hole in the arm, and then attached this to a force meter to get the stall torque. All the motors were tested with essentially the same power source – two AA batteries.

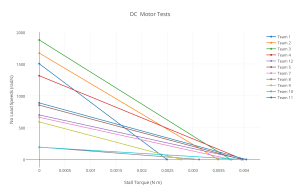

I then had the students share their data using a Google Spreadsheet and I compiled the data – here it is on Plotly:

There is obviously some variability in the motor performance, but its hard to tell if any of the motors give a distinctive advantage over the others because I suspect that the data is not that reliable unfortunately. I do suspect that the angular speed data might be inaccurate due to the fact that we were getting some very differing results from the Photogate. Although we made the sampling rate as rapid as possible, I still am not confident that the Photogate was able to read the blocking of the laser accurately – the motors spin VERY fast (upwards of 5000 RPM’s when not loaded). I’m also not sure if the data then could then be used in any instructive way to help students make design decisions about their dragsters.

Although this may seem like a failure, it did allow the students to identify at least two motors that we knew were malfunctioning, so we were able to swap those out before the competition.

For Next Year

I think at this point I would want to make some changes to this activity. Although it was somewhat helpful in giving the students a direct interaction with data associated with the performance of a DC motor, and how that performance is calculated at the product of the torque and angular velocity, I’m not sure that the activity supplied data that was good enough to then use as an input factor in the competition. For example, I didn’t feel confident about allowing students to use the calculated maximum input power as a scaling factor for their dragster race time.

Perhaps next year, we can find the funds to purchase a high precision, digital torque meter, or find the time and money to build our own “analog” torque/speed meter like the one that MIT designed. All in all, I’d say this activity was partially successful.